Branchhead is a bygone term for the grassroots. It’s grounded in the history of progressive Southern politics. Specifically, it refers to communities that were rural, remote and isolated, inhabited by farmers and working-class folks, those who lived at the branchheads of creeks that formed tributaries to the rivers on which industry depended.

I encountered the term studying the history of my home state of North Carolina, a place many outsiders know for our recent reactionary state politics, but a place I’ve always been proud of for our history of relative progressivism.

In 1948, W. Kerr Scott, a farmer from Alamance County, took on the state’s Democratic (Dixiecrat) establishment and won the gubernatorial primary. He beat the political machine by appealing to the rural base from which he hailed; his supporters were known as “Branchhead Boys.” Scott campaigned on a liberal platform to “get the farmer out of the mud so famers could get to church and farm children to school.” In his time as governor, from 1949 to 1953, he succeeded in moving forward an ambitious program that paved rural roads, deployed rural electrification and telephone service and improved health and education. His accomplishments planted the seed that made it possible, a few years later, for the liberal Democrat Terry Sanford to be elected governor on a platform that eschewed the race-baiting of the day.

This history has lessons to teach us about being bold and building a base of support among people who are chronically underserved and underestimated.

What does this have to do with information ecosystems?

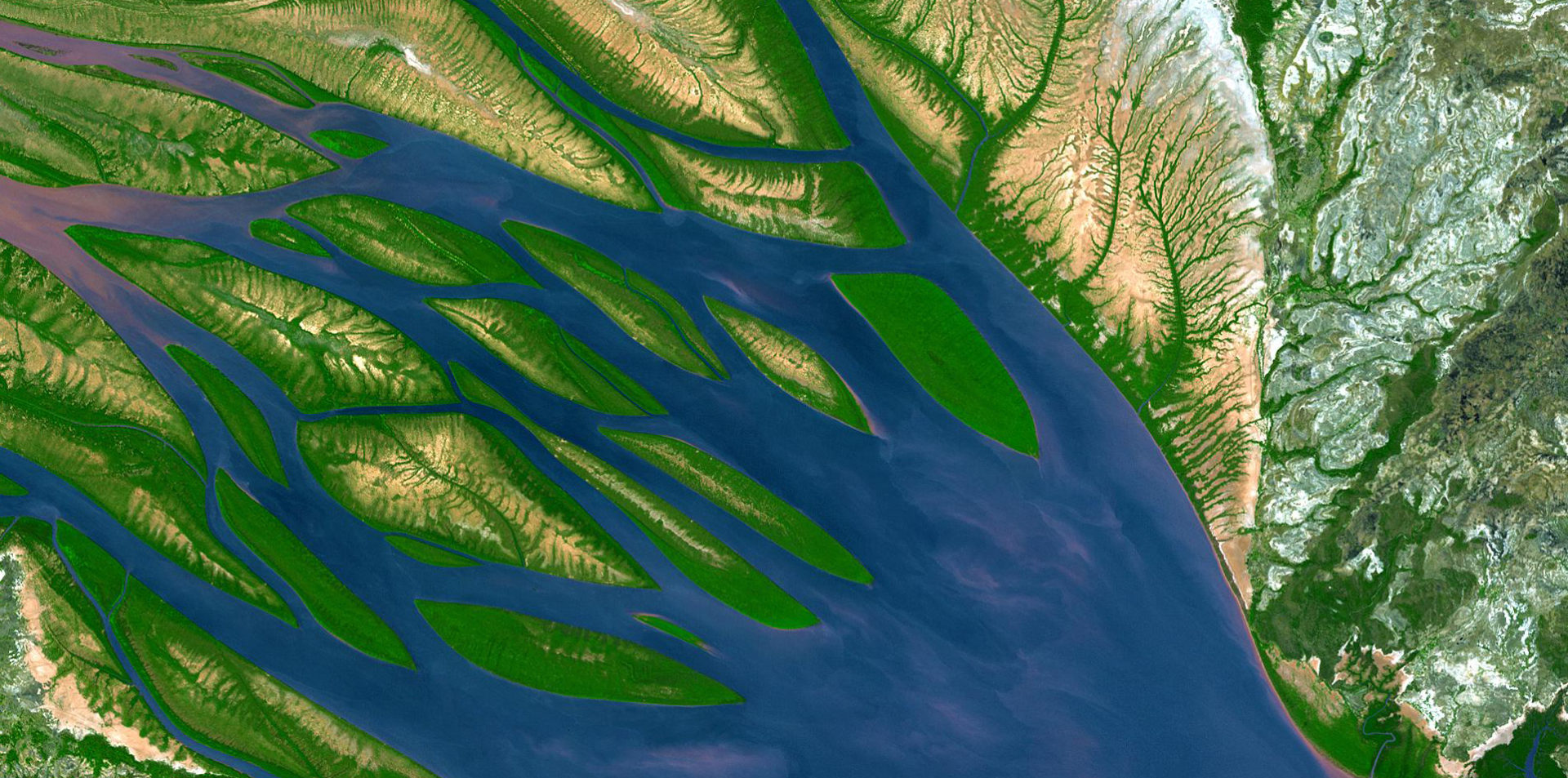

Beyond this, I chose the name Branchhead because it’s evocative of ecosystems.

When we think of “the media,” we often think of the mainstream: the national media, whether left, right or center. But what constitutes the mainstream? And how could it be different, how could our national conversation be better, if the sources that constitute the mainstream were healthier and more representative of our communities?

The branchheads are places where the tributaries begin. They are small, delicate and remote. They follow the contours of the land and flow into greater bodies, forming the rivers and eventually feeding the sea.

Information flows in this way. What we think of as news is the filtered product of all kinds of information: public records, eyewitness testimony, policy, lawsuits, interviews, research and raw human experience. Whose stories get told and which facts circulate depend upon the infrastructure in place to record and share them. The news of one community is a tributary that flows into the larger stream of civic life.

I believe that our democracy cannot function without quality local news. I’ve devoted my career as a journalist, policy analyst, researcher and organizer to strengthening local news ecosystems. I’ve learned that local news cannot thrive without strong ecosystems of information within local communities.

Whoever you are trying to serve, and whatever you are trying to accomplish, you are working within an ecosystem of information.

If you want to inform, engage and empower people — especially those who are frequently left out of the conversation — then I want to help you.

Together we can build new infrastructures and stronger communities.

Check out my offerings and contact me for more information.